The Covenants

In our exploration of faith and the immutable nature of God's Word, we have established that the Word of God remains constant—unchanging through time.

This constancy is reflected in the triune nature of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, who are eternally consistent, yesterday, today, and forever. This unchanging nature extends to the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, which remains steadfast across all ages. This continuity is a cornerstone in God's plan of salvation, a divine blood covenant offered to humanity.

To delve deeper into this concept, it is essential to define and understand the nature of a covenant. A covenant is more than a mere agreement or contract; it is a solemn commitment, often sealed with an oath, involving mutual obligations and promises. The Hebrew word for covenant, BeRiTh בְּרִית, found approximately 300 times in the Tanakh (Old Testament), is believed to originate from an Assyrian term meaning to bind or fetter, suggesting a profound and binding commitment. The King James Version of the Bible mentions 'covenant' 319 times, underscoring its significance in biblical texts.

The Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible describes a covenant as “a solemn agreement between two or more parties, made binding by some sort of oath.” Similarly, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary defines it as “an agreement enacted between two or more parties in which one or both make promises under oath to perform or refrain from certain actions stipulated in advance.” In Hebrew, the phrase Karat Berit, meaning “to cut a covenant,” often accompanies covenant-making, indicating the sacrificial rituals that were part of this solemn act.

Biblical covenants vary in nature and context. For instance, the covenant between Laban and Jacob was symbolized by a heap of stones, serving as a tangible witness to their agreement. Covenants can exist between individuals, tribes, and even kingdoms. A significant example from Old Testament times, which remains relevant today, is the Ketubah contract, a covenant of Holy Matrimony between husband and wife.

To many people step into a marriage without God, A marriage with God involved is not just a contract between two people and their State issued wedding license. A marriage in which God is invoked and involved becomes a Holy act, from which we then also can receive the word of “Holy Matrimony”.

To many people step into a marriage without God, A marriage with God involved is not just a contract between two people and their State issued wedding license. A marriage in which God is invoked and involved becomes a Holy act, from which we then also can receive the word of “Holy Matrimony”.

A marriage which is sanctified, holy, because God is an integral part of it.

This leads to an important distinction between marriage and Holy Matrimony. While many enter into marriage, a union recognized by the state, Holy Matrimony involves a deeper, spiritual dimension where God is an integral part. This sanctified union transcends a legal contract, becoming a holy covenant blessed by God's presence.

Entering into a Covenant with God elevates the participants to partners in fulfilling the covenant, with God's Holiness imbuing the agreement. This is known as Kiddushin, sanctifying both the covenant and its participants. To be sanctified is to be set apart for a special purpose, a calling to a holy life. For Christians, this means that upon conversion, one is dedicated to a life of service, striving to emulate Jesus Christ, walking in His path, and speaking His truth, in contrast to worldly values.

Christians are called to live a holy life, making every effort towards sanctification, even though absolute perfection may not be attained in this life. The ultimate fulfillment of sanctification occurs with Christ's return, when believers are granted glorified bodies. This concept is rooted in Old Testament teachings, as seen in Leviticus 11:44 (KJV), which calls for holiness.

Leviticus 11:44 (kJV)

“For I am the Lord your God: ye shall therefore sanctify yourselves, and ye shall be holy; for I am holy: neither shall ye defile yourselves with any manner of creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.”

A pivotal moment in the history of covenants is found in the encounter between Abram and Melchizedek, the king and High Priest of Salem (now known as Jerusalem). This event, recorded in Genesis 14:18-23 (CEB), marks a significant interaction in the unfolding of God's covenantal relationship with humanity.

A pivotal moment in the history of covenants is found in the encounter between Abram and Melchizedek, the king and High Priest of Salem (now known as Jerusalem). This event, recorded in Genesis 14:18-23 (CEB), marks a significant interaction in the unfolding of God's covenantal relationship with humanity.

Genesis 14:18-23 (CEB)

“Now Melchizedek the king of Salem and the priest of El Elyon had brought bread and wine, 19 and he blessed him, “Bless Abram by El Elyon, creator of heaven and earth; 20 bless El Elyon, who gave you the victory over your enemies.”

Abram gave Melchizedek one-tenth of everything. 21 Then the king of Sodom said to Abram, “Give me the people and take the property for yourself.”

22 But Abram said to the king of Sodom, “I promised the Lord, El Elyon, creator of heaven and earth, 23 that I wouldn’t take even a thread or a sandal strap from anything that was yours so that you couldn’t say, ‘I’m the one who made Abram rich.’”

Abram's encounter with Melchizedek, the priest of the Most High God (El Elyon), is a significant moment in biblical history. Abram's act of giving a tenth to Melchizedek was an acknowledgment of God's sovereignty and Melchizedek's priestly authority. This act of faith and reverence stands in stark contrast to Abram's interaction with the King of Sodom. Abram refused any reward from the King of Sodom, adhering to a vow he had made to God, ensuring that his wealth and success could only be attributed to the divine providence of God, not to human alliances or spoils of war.

Despite Abram's wealth and status, he lamented to God about his lack of a biological heir. This concern was profound in Abram's culture and personal life, as an heir was seen as a continuation of one's legacy and blessings. In response, God led Abram outside and promised him descendants as numerous as the stars in the sky, symbolizing an immeasurable and enduring legacy.

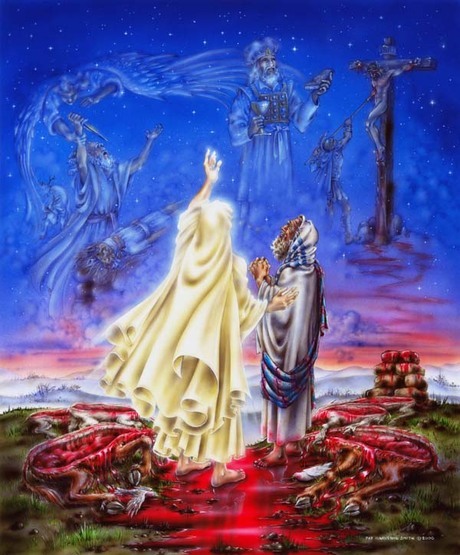

Abram, though a man of great faith, exhibited human skepticism when he questioned God's promise regarding the land. This moment of doubt did not please God, yet it led to a pivotal event: the establishment of a blood covenant between God and Abram. This covenant was not only a promise but also a prophetic foreshadowing of the trials and tribulations that would befall Abram's descendants, including their 400-year bondage in Egypt.

The covenant ceremony was profound and symbolic. Abram prepared the sacrificial animals, dividing them as was customary in ancient covenant rituals, and waited for God to seal the covenant. During this time, Abram diligently protected the sacrificial animals from predators, demonstrating his commitment and readiness to uphold his part of the covenant.

However, as night fell, Abram was overcome by sleep. In this state of vulnerability and rest, God, in His infinite wisdom and mercy, completed the covenant. God's presence, symbolized by a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch, passed between the pieces of the sacrifice. This act signified God's unilateral commitment to the covenant, even as Abram slept. The smoking fire pot and the flaming torch represented God's purifying presence, a refiner's fire that cleanses and sanctifies.

The flaming torch, in particular, is prophetically seen as a representation of Jesus Christ. This imagery foreshadows the New Covenant established through Christ, who is often referred to as the Light of the World. The refiner's fire symbolizes the purifying and sanctifying work of Christ, who cleanses us from sin and personal impurities, ensuring that the covenant is upheld in divine righteousness and purity.

Malachi 3:1-3, 10-12, 17, 18 (AMP)

“Behold, I send My messenger, and he shall prepare the way before Me. And the Lord [the Messiah], Whom you seek, will suddenly come to His temple; the Messenger or Angel of the covenant, Whom you desire, behold, He shall come, says the Lord of hosts.

2 But who can endure the day of His coming? And who can stand when He appears? For He is like a refiner’s fire and like fullers’ soap;

3 He will sit as a refiner and purifier of silver, and He will purify the priests, the sons of Levi, and refine them like gold and silver, that they may offer to the Lord offerings in righteousness.

10 Bring all the tithes (the whole tenth of your income) into the storehouse, that there may be food in My house, and prove Me now by it, says the Lord of hosts, if I will not open the windows of heaven for you and pour you out a blessing, that there shall not be room enough to receive it.

11 And I will rebuke the devourer [insects and plagues] for your sakes and he shall not destroy the fruits of your ground, neither shall your vine drop its fruit before the time in the field, says the Lord of hosts.

12 And all nations shall call you happy and blessed, for you shall be a land of delight, says the Lord of hosts.

17 And they shall be Mine, says the Lord of hosts, in that day when I publicly recognize and openly declare them to be My jewels (My special possession, My peculiar treasure). And I will spare them, as a man spares his own son who serves him.

18 Then shall you return and discern between the righteous and the wicked, between him who serves God and him who does not serve Him.”

Another confirmation of this covenant and the cleansing fire of the Lord we find in the book of the prophet

Another confirmation of this covenant and the cleansing fire of the Lord we find in the book of the prophet

Zechariah 13:9 (AMP)

“And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined and will test them as gold is tested. They will call on My name, and I will hear and answer them. I will say, It is My people; and they will say, The Lord is my God.”

The refining process that began with Abram's covenant with God indeed represents an ongoing journey, one marked by faith, trials, and growth. This journey is vividly illustrated in the unfolding narrative of Abram (later Abraham) and Sarai (later Sarah), particularly in Genesis 16. Despite the remarkable promise God had made to Abram, the fulfillment of this promise seemed to be delayed, leading Abram and Sarai to take matters into their own hands.

At the age of 86, Abram fathered a child with Hagar, Sarai's Egyptian maidservant. This decision was borne out of impatience and a human attempt to fulfill divine promises through their own means. Sarai, unable to conceive, offered Hagar to Abram as a second wife, solely for the purpose of providing an heir. This action, while culturally acceptable at the time, was a deviation from the monogamous nature of Abram's marriage to Sarai up to that point.

The birth of Ishmael to Hagar, however, was not the fulfillment of God's covenant. This act of taking a second wife to bear a child was a manifestation of Abram and Sarai's struggle to fully trust in God's timing and promises. It reflects a common human tendency to rely on our own understanding and efforts when divine plans do not align with our expectations or timelines.

Genesis 17:1-5 (AMP)

“When Abram was ninety-nine years old, the Lord appeared to him and said, I am the Almighty God; walk and live habitually before Me and be perfect (blameless, wholehearted, complete).

2 And I will make My covenant (solemn pledge) between Me and you and will multiply you exceedingly.

3 Then Abram fell on his face, and God said to him,

4 As for Me, behold, My covenant (solemn pledge) is with you, and you shall be the father of many nations.

5 Nor shall your name any longer be Abram [high, exalted father]; but your name shall be Abraham [father of a multitude], for I have made you the father of many nations.”

The transformation of Sarai into Sarah, meaning "princess," and the birth of Isaac, whose name means "laughter," are pivotal in the narrative of God's covenant with Abram. Isaac's birth was a fulfillment of God's promise, a miracle that brought joy and laughter, especially considering Abram's initial reaction of disbelief at the prospect of fatherhood at such an advanced age. This event underscores a fundamental truth about divine covenants: God is unfailingly faithful to His promises, regardless of human circumstances or limitations.

The story of Abram and Sarah teaches us about the nature of faith and trust in God. It challenges us to consider our own faithfulness and trust in God's provisions. Like Abram, who chose to forgo the wealth of Sodom, we are called to discern and sometimes reject immediate prosperity, trusting instead in God's provision (Jehovah Jireh). Our faith is often refined through trials and challenges, stripping away pride and self-reliance to reveal a purer, more humble reliance on God's grace and provision.

Genesis 12:2-3 (AMP) “2 And I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you [with abundant increase of favors] and make your name famous and distinguished, and you will be a blessing [dispensing good to others].

3 And I will bless those who bless you [who confer prosperity or happiness upon you] and curse him who curses or uses insolent language toward you; in you will all the families and kindred of the earth be blessed [and by you they will bless themselves].”

The covenant promises of God, as seen in the life of Abram, extend beyond his immediate lineage. In Genesis 12:2-3 (AMP), God's promise to Abram is not only for his descendants but for all nations, indicating a universal aspect of God's covenantal plan. This inclusivity is further emphasized in the New Testament, where Christians, as spiritual descendants of Abraham, are grafted into this covenant, becoming partakers in the promises of God.

The biblical narrative presents various covenants that God established throughout history, each with specific promises and stipulations:

- The Adamic Covenant: God's grant of dominion over the earth to Adam and his descendants.

- The Noahic Covenant: God's promise never to destroy the earth by flood again.

- The Abrahamic Covenant: The promise of land, numerous descendants, and blessings to the nations.

- The Mosaic or Sinaitic Covenant: God's laws given at Sinai, promising blessings for obedience and curses for disobedience.

- The Land Covenant: The promise of the land of Zion to the Israelites, contingent upon their obedience.

- The Davidic Covenant: Establishing David's dynasty, the promise of the Messiah, and the temple.

- The New Covenant: Inaugurated by Jesus Christ, it promises a new heart and spirit, gathering all nations back to Zion.

- The Eternal Covenant of Peace: The culmination of all covenants, establishing God's throne in the New Jerusalem, with Jesus reigning eternally as the Prince of Peace.

These covenants, viewed through the lens of dispensationalism, reveal a consistent, unchanging God who works through different eras and methods to accomplish His divine plan. Each covenant builds upon the previous, culminating in the ultimate fulfillment of God's redemptive work through Jesus Christ. This continuity and faithfulness of God across different dispensations affirm that His promises and covenants remain valid and active, guiding believers in their faith journey and shaping their understanding of God's eternal purpose.